In 1677 two hundred and thirty Quakers from Yorkshire, England disembarked the HMS Kent at “Racoon Creek” in “West New Jersey”. These people founded what is now Burlington County, NJ. One of them, a “Crofter” named John Cripps prospered so mightily here that his “Plantation Mount Holley” became Burlington County’s seat of government: Mount Holly, NJ. Just how did this Yeoman Crofter become a real estate tycoon? It’s complicated.

Mount Holly is the County seat of Burlington County, New Jersey. It’s snuggled in what was historically referred to as “West Jersey”. If you’ve ever wondered why there is such an institutionally-rigid characterization of “North Jersey” and “South Jersey” there’s a good reason. Historically, the colony was known as “East Jersey” (the upper part) and “West Jersey” (the lower part). Eventually, more sensible North / South references became common parlance.

This nomenclature has much to do with King Charles II of England (Born: 1630/ Died: 1685), who was an inveterate gambler and three of his loyal friends to whom His Majesty owed large sums of gold. The first two of these card sharps, Lords Berkeley and Carteret, quite understandably, wanted to get paid. At this point in the story we introduce James, Duke of York (Born: 1633/ Died: 1701) – the younger brother of King Charles II. In 1664 the Duke of York was given New Jersey – lock, stock and barrel – by King Charles II. James was King Charles’ little brother. James, Duke of York, got all of New Jersey, from “Cape Mey” to “Highpoint” at the New York border.

James didn’t especially want New Jersey – he preferred his palatial estates in England and Scotland. He promptly offered New Jersey real estate up to settle some of his big brother’s (the King’s) gambling debts when he learned about the money fix brother Charlie was in. It was a grand gesture that had big historical consequences.

James, Duke of York, conveyed New Jersey as a Proprietary Colony to Lords Carteret and Berkeley in 1674 in “Accord and Satisfaction” of the gambling debts owed to them by King Charles II.

This Proprietary Colony was divided into two separate provinces, “East Jersey” (up) and “West Jersey” (down), each governed by its own Board of Crown Proprietors. The two Boards sold land in their respective halves to individuals through “Proprietary Deeds” in which buyers memorialized their “Proprietary Share” ownership of the Colony (ie. a percentage – a “tenth” or a “hundreth” or combination thereof). Land ownership was registered like shares of stock.

East Jersey (up) was Lord Carteret’s bailiwick. He named Elizabeth, New Jersey after his wife, Elizabeth. The area became a burgeoning Port Town and trade center and, in addition to his sales of Proprietary Deeds, Lord Carteret became quite wealthy. Of course, his connections at Court in London certainly didn’t hurt him either. In 1673 Lord Berkeley conveyed a large portion of his land holdings in West Jersey to Sir John Fenwick, setting the stage for a colossal land title feud with William Penn years later.

King Charles II continued to indulge his gambling proclivities. No sooner had his brother James bailed Charles’ chestnuts out of the fire with Lords Berkeley and Carteret, the English Monarch admitted that he owed the Admiral Sir William Penn even more gold than he ever owed Lords Berkeley and Carteret combined (apparently His Majesty was in desperate need of Gamblers Anonymous or professional therapy).

Of course, Admiral Sir William Penn was not disposed to press his claims “at law” in the English Courts against his reigning monarch – but he demanded payment all the same. A compromise of sorts was arranged.

At this point we must pause and consider what is happening in England at the time. These are the days of the “Glorious Revolution” and all manner of radical and violent Protestant versus Catholic rancor. Two religious sects in particular are causing the Crown an enormous pain in its ample royal ass.

The Puritans – extremists who tolerated literally nothing secular and were famously miserable to live with (sometimes called “Roundheads”) – supported Cromwell in the English Civil War. They were ultimately rebuffed in the “Restoration” but nevertheless continued to be so unpopular they left England in droves for the New World – not always voluntarily. You know the story from there – Plymouth Rock, the First Thanksgiving, John Smith, Pocohontas, etc.

The other religious sect that was inflicting its share of Royal and cultural hemorrhoids in England was the “Religious Society of Friends”.

Because reading the Word of God in their Bibles caused them to “quake and tremble” with faith, they were called Quakers. Like the Puritans, they were a rather stubborn lot and their distrustful view of the Monarchy made them suspect in the extreme. Quakers were vocal, literate and contemptuous of secular values. They hated the Church of England. English society as a whole was eager to off-shore both Puritans and Quakers to greener pastures in the wilds of North America. Charles II and his advisors wanted nothing to do with religious extremists of any stripe and decided that loading them all onto creaky boats for long sea voyages was a really good idea.

Charles II’s creditor (The King owed him millions in todays currency), Admiral Sir William Penn, had a son, William Penn the Junior. He was an influential writer and a founding member of the “Religious Society of Friends”. Quaker William Penn the Junior had an idea: eastablish a colony of “Friends” (how Quakers referred to each other) in the New World. He envisioned a mass emigration of English Quakers.

Charles II owed Admiral Penn a lot of money. Admiral Penn’s son was an extremely influential leader of one of two religious sects that the Crown wanted out of England permanently. Viola! In 1681 Charles II “paid” Admiral Penn his winnings by Deeding him what is now Pennsylvania, Delaware and the remaining scraps of “West Jersey” that Lord Berkeley didn’t already own. Admiral Penn then shipped his troublemaking son off to the New World and Pennsylvania was born. Quakers started their proliferation throughout most Southern NJ Counties and beyond from there.

This may be the historical reason for Jersey’s up /down “Eternal Divide” : South Jersey being predominately Quaker and north Jersey mostly Anglican / Protestant in the 1600s. Die-hard Puritans and radical Calvinists obsessed with their “New Zion” would stake their claim further North in New England.

Religious differences back then were a big deal and often the catalyst for entire geographic enclaves. Maryland, for example, was established as a haven for Roman Catholics. Co-religionists in the 1600’s generally preferred each other’s company after the resentment and discrimination they’d experienced in England. Their memories were still raw. Only Rhode Island held itself out as a kind of religious neutral zone.

It is impossible to overestimate the influence William Penn and his Quaker followers had on early “Central Atlantic” NJ Colonial history. Quakers brought to the New World a unique and relatively tolerant (compared to the Puritans) outlook. They were a self-sufficient, industrious and unified people – motivated by high ideals and a general disdain of government. They were anti-war and generally resisted serving in any army.

Quakers imposed no death penalty and their prisons or “Gaols” were crafted more for rehabilitation and reflection than punishment. Quaker “Meeting Houses” (they didn’t have Churches) became microcosms of government in their New World.

Quakers helped one another and believed that the success of one of their flock raised everyone’s boat. Comparing historical accounts of Puritan towns in New England with Quaker communities in what later became the “Commonwealth” of Pennsylvania (William Penn hated the word “State”) presents glaring and sometimes unsettling contrasts. Puritan ideas about law, punishment and witchcraft alone are eye-opening. Puritans and Quakers were, philosophically at least, oil and water.

It is clear why England banished the Puritans – and it’s no mystery why Benjamin Frankiln later found Quaker Philadelphia so “agreeable” compared to his native Boston. Quaker values suited Franklin. In Pennsylvania he found just the right mixture of order, common purpose, liberal thought and self-reliance. The arrival of Lutheran Germans also helped leaven the psychology of these “Central Atlantic” settlers. Their combined hard work ethic, industry and strong sense of of community built a solid foundation for colonial success.

William Penn died in 1718. His heirs, John and Thomas Penn, did business differently than their late father. In 1730 they embarked on a ponzi scheme to foist land deeds back-dated to the 1680’s on Lenepe Indian “polities” or tribal subdivisions that were patently fraudulent. The so-called “Walking Purchase” relieved the Leni Lenape Indians of any claims whatsoever they had on Southern New Jersey and Delaware. The Lenape Indian’s sporatic resistance to colonial grip on their land, even in the courts, ultimately resulted in – no pun intended – their “Walking” away.

The foregoing, then, adequately describes the “lay of the land” when in Summer, 1677, two hundred and thirty Quakers from Yorkshire, England boarded HMS Kent in Bristol and handed their passage monies to Master Gregory Marlow (Senior Officer, Pilot and Captain). They would later journey (with fifty other passengers) first to New York (then known as New Amsterdam), Perth Amboy and, finally, around the “Cape Mey” (named after Dutch Captain Cornelius Jacobsen Mey in 1611) and up the Delaware River.

They disembarked at a place later called “Salem” (now Salem County), from the Hebrew “Shalom” for “Peace”. The Quakers then proceeded on foot and canoe further up the Delaware River to “Racoon Creek” (Indian name: “Rancocas”). Over two hundred of them settled in that area – now known as Burlington.

The Yorkshire Quakers apparently settled in the “First Tenth of Proprietary from Assinpunk to Rancocas”. A group of London Quakers settled the “Second Tenth from Rancocas to Timber Creek”.

West Jersey was “partitioned” into five territories by the original Documents Proprietary given to Admiral Penn is satisfaction of the King’s debt to him. Each of the five territories was called a Tenth. The five Tenths stretched from Assunpink Creek (a tributary of the Delaware River) southward to the Cohansey River (at the North shore of Delaware Bay). all fronting the East Bank of the Delaware River. Obviously, the original five Tenths of West Jersey was a substantial piece of real estate.

(*See Clement, John. Sketches of the First Immigrant Settlers in Newton Township, Old Gloucester County, West New Jersey. Genealogical Publishing Company, Baltimore, Maryland. Re-issued 2002 also

Hargreaves-Maudsley. Bristol and America. A Record of the First Settlers in the Colonies of North America, 1654-1685. London, 1899.

Fernow & Berthold. West Jersey Settlers. New York Genealogical Society Records. Volume 30:2 (April, 1899, pages 114-118) and Volume 30:3 (July, 1899, pages 175-176).

R.S. Glover. A Record of the First Settlers in the Colonies of North America, 1654-1685. London. Reprinted, Genealogical Publishing Company, Baltimore, Maryland, 1967. Reprinted, 1978.

Revel’s Book of Surveys. NJ State Archives, 225 West State Street, PO Box 307, Trenton, NJ 08625-0307; OV8, Folder 6, Series SNJSA001)

This was to be the first of many such landings of Quakers on what is now Burlington County, New Jersey. Armed with their faith and some (very) rudimentary firearms, William Penn’s acolytes commenced their diaspora throughout Southern New Jersey, the entirety of the Thirteen Colonies and what would later become the United States of America. In the one hundred years that would span their arrival in Burlington County and The Declaration of Independence, Quakers would transform their New Jerusalem into a bulwark of industry, learning and prosperity.

Returning to 1677, then, we re-focus on Yeoman Crofter John Cripps, his wife Mary and their two children, pitching their tent at Racoon Creek, taking inventory of their meager property and dreaming of life to come in their New World. His journey is the thread that binds this historical account together.

Cripps is a “Crofter” – a farmer of a rented farm. Today we’d call him a “share-cropper”. A “Croft” (Scottish colloquial) usually refers to a plot of arable land attached to a house and sharing a common “pasturage” with other abutting subsistence farmers. A share-cropper “shares” his crop yield with his landlord, thereby paying his rent for the roof over his head and keeping a portion of food for his family survival.

Being a “Yeoman” is significant. John Cripps is a freeman, not an indentured servant or other class of servile souls impressed to work off their debts to a landed Gentryman back in England. Often such indentured persons could labor as long as twenty years to discharge a particular debt or obligation to a wealthy businessman or “Titled” member of English polite society back home.

Generally, Quakers eschewed such bondage on religious grounds, hence we can probably conclude with certainty that their West Jersey settlement on the Rancocas River was populated with Yeoman (and Yeo-woman) faces only.

For our chronological purposes, 1677 is the starting point. Let’s review Revel’s Book of Surveys from the New Jersey State Historical Archives, 1677 onward, to track the amazing success of John Cripps. What follows are his real estate transactions and those of his son, Nathaniel. Exact spelling, punctuation and order from the New Jersey Colonial Documents, Liber B, in the NJ State Archives is reproduced. (Note: This chronicle does not set forth the “consideration” – or money changing hands – involved in each transaction).

– 1681, May 19. Lawrence Morris, of 50 a., E., the road from Rancokus Cr.to the great meadow, W., and N., Henry Ballenger, S. Richard Fenimore. This prcell transmitted to JOHN CRIPPS as see Book B., p. 29.

– 1681, April 18. To JOHN CRIPPS, of 300 a., S. Rancokus Cr., the line running on a S. S. W. course “through a swamp, wherein growes store of Holley and within said Tract is a mountaine to which Province East, South and West and North send a beautifull aspect named by the owner thereof MOUNT HOLLEY”.

– 1681, Aug. 15. for JOHN CRIPPS, of 100 a. on Dellaware R. against Sepassings Island, called Laboure Point, E. a creek.

– 1681, Feb. 6. Hannah Salter of Tawcony, Penna., widow, John Hooton of Mansfield, W. J., yeoman, and John Snowden of Mansfield, yeoman, son of Wm. Snowden of Edwinboro, dec’d, to JOHN CRIPPS of Burlington, yeoman, for 1-12 of share or half of the preceding 1-6.*

(*Preceding 1-6 in register was: 1677 (29th year of Charles II) July 7. Deed. Richard Mew of Ratcliff, Co. of Middlesex, merchant, to Wm. Snowden of Edwinsboro, Co. of Nottingham, yeoman, and John Hooton of Skegby, same Co., husbandman, for 1-6 share of West Jersey.)

– 1681, June 19. Anna Salter of Korkanney, N. Y., widow to JOHN CRIPPS for the preceding 1-32 of a share.

– 1680, Nov. 25. John Smyth of Christeene Creek, yeoman, to JOHN CRIPPS of Burlington, yeoman, for 1 1/2 acres in Burlington, E. High St., N. Matthew Allen, S. John Woolston, W. another street.

– 1687, Feb. 18. Thomas Budd, merchant, to NATHANIEL CRIPPS, yeoman, both of Burlington, for 100 acres in Burlington Co., part of the land bought of Edward Byllinge and Trustees March 2, 1676-7.

– 1695, Aug. 8. Willam Biddle of Mount Hope, Burlington, Co., merchant, to NATHANIEL CRIPPS, for 2 acres on the Island of Burlington.

– 1693, Oct. 10. Deed. Thomas Lambert, senior, of Nottingham Township, tanner, to Barnard Lane of Burlington, butcher, for 40 acres in Burlington town bounds, between Henry Stacy, NATHANIEL CRIPPS and Samuel ffurnis.

– 1682-3 March 22. JOHN CRIPPS to Lawrence Morris, both of Burlington, yeomen, for 200 acres to be taken up as part of 1-12 of a share in the Second Tenth, bought of Anna Salter February 5-6, 1681-2.

– 1682-3 March 21-22. Mem. of Deed. JOHN CRIPPS to Lawrence Morris, for 200 acres, part of 1-12 in the Second Tenth, bo’t of Anna Salter Feb. 5-6, 1681-2 (supra. p. 7), to be surveyed for grantee, in exchange for 50 acres of said Morris near Mount Holly in the Second Tenth.

– 1682-3 March 13-14. JOHN CRIPPS to Walter Clarke, for a lot in Burlington Town, S. W. and S. E. Samuel Jenings, N. E. Edmond Stuart, 112 1/2 acres.

– 1681-2 Feb. 5-6. Hannah Salter, John Hooton and John Snowden to JOHN CRIPPS, for 1-12 of a share, being 1/2 of 1-6 formerly bo’t by Wm. Snowden and John Hooton of Rich’d Mew, July 6-7, 1677.

– 1682 April 14-15. Anna Salter to William Haige, for two cottages in Burlingtonin the tenure of George Bartholowmew, with the lots, whereon they stand, part of said Anna’s 1-12 of a share in the Yorkshire Tenth of Burlington; also a houselot near JOHN CRIPPS there, part of her 1-12 share in the London Tenth and all the lots lying to the Dellaware R., belonging to said Hannah for her waterlots of the 1-12 in the London Tenth, in exchange for 300 a. of said Haige’s in West Jersey.

(*Deeds in England at the time set forth lands conveyed in “Parts” – as in “90 Parts of 100 Parts”, etc. A full “Proprietary Share” under a Colonial Proprietary Deed was an interest known as a “Hundreth Part”. Lesser parts of the “Hundreth” (such as 1/12th, 1/6th) or a definitive number of acres was also possible. Ten “Proprietaries”, for example., amounted to One Tenth of the entire Province of West Jersey.)

Clearly, the most significant property is the April 18, 1681 purchase “for JOHN CRIPPS” of 300 acres “S. Rancokus Cr., the line running on a S. S. W. course through a swamp, wherein growes store of Holley and within said Tract is a mountaine to which the Province East, South and West and North send a beautiful aspect named by the owner thereof Mount Holley”.

It appears John Cripps scored himself some choice real estate here. So choice, in fact, that the Chronicle of Deeds recounted in Revel’s Book of Surveys memorializes its “beautiful aspect” on a “Mountaine” overlooking views “East, South and West and North”. Finally, the name of this special parcel is revealed: Mount Holley.

There is anecdotal evidence that Quaker John Cripps named his “Mountaine” paradise Mount Holley not only for the wild “store of Holley” that grew there, but to evoke a Biblical allusion to “Mount Holy”, ie. the “Holy Mount” in Jerusalem. To a devout Quaker, calling his home Mount Holly would have proclaimed in faithful affirmation that this place was, indeed, the “New Jerusalem” of the New World. This, then, was literally to be his “Shining City on a Hill”. As we shall see, John and Nathaniel Cripps would add to acreage their estate. In fact, land transfer entries would come to simply just identify it as the “Plantation”.

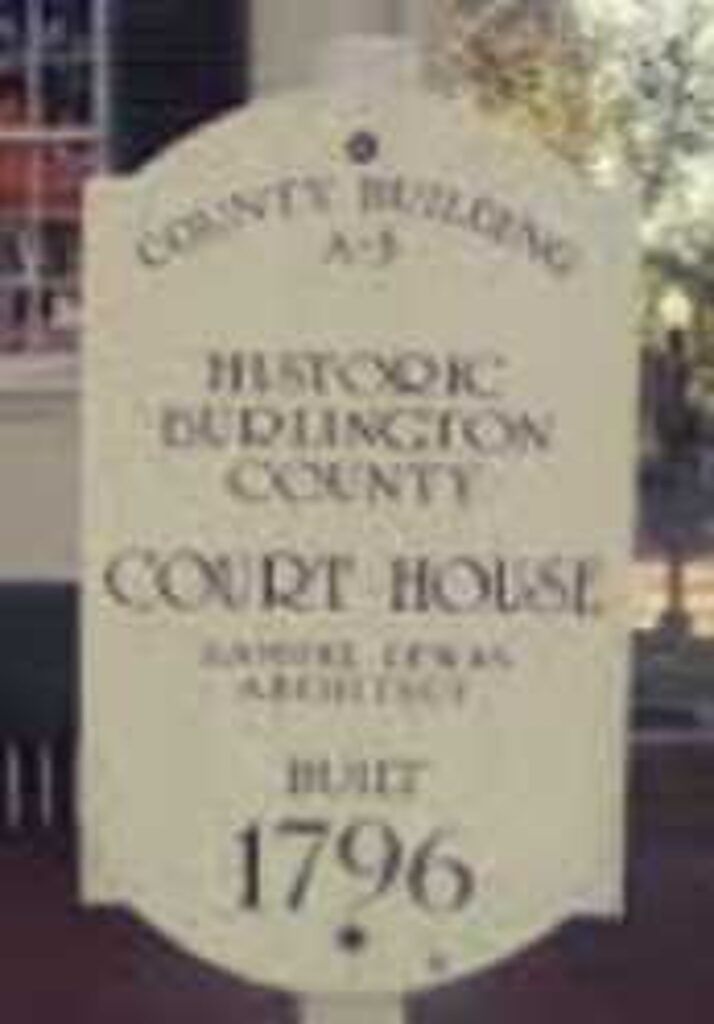

Mount Holly, NJ, then, is born in 1681. Not as a city (the town around it was formally incorporated as Northampton in 1688 and later renamed Mount Holly, NJ in 1931), but as a private residence and an idea.

Thereafter, John Cripps continues buying up New Jersey property. Folios of original “Indentures” – an old timey word for Deeds – extant in the New Jersey Archives in Trenton reveal that John Cripps’ appetite for land titles was prodigious. These records are preserved in “Folios” in the NJ State Archives on microfiche. They are hand-written in the arcane script of the time and generally lack any record of “consideration” (money changing hands) that was paid for each deal. Nevertheless, these records speak volumes.

– B(WJ): Folio 532: March 19, 1695. Matthias Dillon to JOHN CRIPPS of Burlington, 100 acres;

– B(WJ): Folio 521: November 5, 1695. John Smyth to JOHN CRIPPS of Burlington, 100 acres;

– B(WJ): Folio 521: February 18, 1685, Thomas Budd to NATHANIEL CRIPPS of Burlington, 100 acres;

– B(WJ): Folio 7 : February 5, 1681, JOHN CRIPPS from Harmah Fallon, 200 acres – consideration paid in English Pounds;

– B(WJ): Folio 20: October 10, 1682, Henry Stacy from JOHN CRIPPS of Burlington, 50 acres;

– B(WJ): Folio 104: February 20, 1685, Brerfall Rowles to JOHN CRIPPS of Burlington, 100 acres;

– B(WJ): Folio 521: November 5, 1695, John Smythe to JOHN CRIPPS of Burlington, 100 and 1/2 acres – consideration paid in English Pounds;

– B(WJ): Folio 521: February 18, 1695, Thomas Budd to NATHANIEL CRIPPS of Burlington, 100 acres;

– B(WJ) Folio 521: August 8, 1695, Wm. Biddle to NATHANIEL CRIPPS of Burlington, 100 acres;

– B(WJ) Folio 536: March 1, 1689, Cotton Boothe to JOHN CRIPPS of Burlington, 100 acres;

– B(WJ) Folio 536: March 19, 1684/5, Mattias Dillon to JOHN CRIPPS of Burlington, 100 acres;

Nathaniel Cripps slowly outshines his father in his appetite for land. Records show him accumulating a veritable smorgasbord of land titles:

– 1684: 5.75 acres on High Street (later Mount Holly);

– 1687: 25 acres / Town Lots on High Street; 25 acres in “Plantation” Mount Holley; 100 acres pasture, Burlington;

– 1694: 180 acres in Northampton, pasture; 27.5 acres Town Lots on High Street;

– 1695: 2 acres on “Plantation” Mount Holley;

– 1700: 14.75 acres on “Plantation” Mount Holley;

– 1708: 500 acres “Indian Land” in Burlington with Thomas Bryant;

– 1714: 10 acres on “Plantation” Mount Holley; 14.75 acres on “Plantation” Mount Holley;

– 1728: 457 acres “Cedar Swamp” in Little Egg Harbor;

– 1737: 300 acres “Salt Marsh” in Little Egg Harbor;

– 1737: 100 acres “Swamp” in Atsion;

– 1739: 245 acres “Salt Marsh” Little Egg Harbor;

– 1740: 245 acres “Marsh” in Little Egg Harbor;

– 1742: 100 acres “Marsh” Little Egg Harbor;

– 1746: 930 acres Northampton pasture.

Impressive – but, as the song goes, the fundamentals apply as time goes by. Where did a Crofter – a share-cropper – get the money to buy all this land? On the timeline of history, he no sooner gets off the boat in 1677 and he starts buying up land like a drunken sailor. Saying “land was cheaper then” is obtuse. Land is, was and always will be (at least in New Jersey) a big ticket item. Multiple purchases of hundreds of acres requires cash monies. Where did someone of such quintessential “humble beginnings” get his seed money, his “grubsteak” to embark on this frenzied binge of land title aquisitions?

As we ponder the mysterious provenance of John Cripps’ wealth, let us bear in mind a few caveats. The Folios and Ledger entries of the day typically did not memorialize Mortgages – although “Shire Clarkes” in England certainly did. Mortgages were fairly common and always recorded in England in the late 1600s. Up in “East Jersey” Mortgages were regularly recorded around this time. Because we are dealing with Quakers, however, the very idea of a Mortgage was probably anathema.

Quakers didn’t “borrow” and lived the Biblical admonition: “Neither a borrower or lender be”. Theirs was an “individualistic” society premised on mutual respect and civility. It seems what they owned they owned “outright’, ie. with no liens or encumbrances. Quakers would probably spot you a few bob for a tankard of rum at the local Pub – but an Instrument of Mortgage was out of the question.

It is probable that if a Deed were encumbered by a Mortgage in the late 1600s, a County “Clarke” here in America would duly record it (or a reference to it). From the lack of such recorded Instruments of Mortgage (or any references thereto in Deeds of the time) we can probably conclude there weren’t any. Real estate transctions were cash on the barrelhead. Purchase-money Mortgages are a recent development – and even today land deals (with no houses or structures on them) are “cash deals” only.

We can, then, eliminate financing as an option for John Cripps. What’s left? Barter? What can a share-cropper offer worth the value of hundreds of acres of land? Bushels of squash or corn? Yams?

Yeoman Crofter John Cripps, then, is an enigma. A conundrum. Did Crofters do such an abundant cash business back in England that Cripps brought with him to America a steamer trunk full of His Majesty’s currency? A real estate investment fund of sorts to propel him forward in his new life? It’s doubtful. If England were such a fruitful, bounteous land he never would have left it in the first place, religion or no religion. It’s more likely he came here as broke and desperate as everybody else of non-royal stock.

Did family “back home” bankroll him? He was what we call today a “subsistence farmer” (“Share-Cropper” carries with it unsavory racial implications these days, hence it is fading from useage). I doubt family back in England (if he had any they’d have probably been as broke as he was) would’ve slipped him any more than a few bucks for a roof over his head and a back yard to grow enough food to keep him, his wife and kids alive. The Cripps family passage money alone was probably astronomical for the time.

I’ve totalled the land transactions that I’ve documented. John and Nathaniel Cripps separately purchased almost four thousand acres of property in “West Jersey”. Not too shabby. Of course there might have been additional titles gained by adverse possession (no longer possible under current laws), swapping acreage and outright confiscation from the weakened Lenape Indian preserves.

Where did he get the money?

I have some theories – but only one of them fits the cold, hard facts.

Even the miracle of compound interest can’t account for how John Cripps’ accumulated money so magically that he could afford his eye-opening land purchases. Honore’ de Balzac, the famous French novelist and playwright, is credited with perhaps one of the truest truisms ever published: “Behind every great fortune, there is a crime”. The first page of Mario Puzo’s, The Godfather, reproduces it front and center to set the mood and context for his Mafia magnum opus that follows.

John Cripps – and his son Nathaniel – were probably smugglers.

Without a doubt they would have coveted farmland, pasture land and building lots. The only wealth in the 1600’s was land wealth, unless, of course, you had access to gold. But to buy land they needed a source of funding that was dependable, substantial and reliable. There are clues here if you study the titles and know the geography.

Mount Holly is not far from the Rancocas River. The Rancocas was used as an inland highway for barges to get lumber and materials to the Delaware River, thence to Philadelphia. Down the Delaware River was – Delaware – and access to the Atlantic Ocean. East Coast ports such as Perth Amboy, Elizabeth, New Amsterdam / New York beckoned. England was over the horizon.

It appears, however, Mssrs. Cripps dreamed bigger than going the long way around the barn of local commerce. They probably wanted to cut out the Delaware trade competition altogether and plant their flag on the Atlantic Coast. For that they’d need a route eastward that was workable relative to their base at the “Plantation” in Mount Holly. A route to a coastal estuary where sea-faring ships regularly stopped to collect the eggs from thousands of Gulls that roosted there. A place where mariners knew well the coastline, deep water pathways and locations of sand bars. A place where Atlantic sailors stopped to supplement their food stores and trade with the Indians who had named it.

That place was Little Egg Harbor.

The Lenape Indians probably – intentionally or unintentionally – showed Cripps the way. Down the logging road that became NJ Route 206 to the “Atsion” wilderness, down the Mullica and Bass Rivers, past Batsto and through the labyrinth of estuarial creeks and waterways that meander their way to the “Little Egg Harbor”.

There, relatively safe and naturally obscured inlets could shelter sea-going ships engaged in plying their trade between New Amsterdam, Boston, Rhode Island, Jamaica and the Antibes in the Carribean or England. All (legal and illegal) manner of commerce – clothing, arms, tools, rum, molasses, information – could be transacted, duty free. Handsome profits would await back in Burlington as Cripps Senior and Junior got the jump on their competitors who were being bled dry by Crown taxmen, middlemen, Delaware River traders and Pennsylvanians.

Look at the Cripps land titles. Little Egg Harbor is virtually their fiefdom, together with the “Salt Marshes”, “Marsh”, “Cedar Swamp” and “Swamp” areas surrounding it as far inland as Atsion (Wharton State Park, Route 206, today). Draw a line from Mount Holly, NJ, through the Pine Barrens and follow the waterways as the proverbial crow flies. Bingo. Little Egg Harbor and its surrounding estuarial, brackish swampland is the pot of gold at the end of this rainbow.

Evidence certainly suggests that West Jersey Crofter John Cripps invented a better mousetrap and parlayed his smuggling savvy into a real estate empire. The “Crofter” in him knew there was no money in growing corn on his own or anybody else’s land. He was after real money. And he got it, by using his brains and muscle. Smuggling wasn’t for the weak or faint hearted. It was dangerous and illegal. A crime for which people were hung by the Crown – and New Jersey was still part of England. The risks were great but so were the profits.

If you study the land titles – especially the building lots – Cripps purchased in what is now Mount Holly, it is clear that the Court House, County Buildings, Old Burlington County Jail and most of Main street (including the so-called “Witches Well” off High Street) were all erected on either the investment plots of John and Nathaniel Cripps or their private “Plantation”, high on its “Mountaine” with its “Stores of Holley” and “beautiful aspect”.

John Cripps was an admirable guy. I propose erecting a bronze statue of John Cripps right across from the Court House. Have him posing in a full Quaker outfit, looking like the guy on the Oatmeal box. Hand on a cane and buckles on his shoes. Frock coat with sash. Maybe a big, broad-rimmed hat on his wig-covered head. A weathered but serene face.

And if you ever find yourself savoring a pint of fine stout at The Village Idiot Brew Pub on Main Street in Mount Holly, NJ – raise your glass in a toast to John and Nathaniel Cripps. After all, you’re sitting in their front yard.

Copyright, 2021. Jon Croft.

(NOTE: *If you know something about this topic, please feel free to email me and discuss your ideas or information. I especially invite any current descendants of Mr. Cripps – or Quaker “Friends”- to make contact if they wish to add or clarify any facts.)